|

cine101 -- 2010 ?

script shots themes images symbols ... Claudia = death ? [ back to filmstudy list ]

|

|

italian cinema (new)

new 2006 *

* 8 1/2 (1963) credits * Guido is a film director, trying to relax after his last big hit. He can't get a moments peace, however, with the people who have worked with him in the past constantly looking for more work. He wrestles with his conscience, but is unable to come up with a new idea. While thinking, he starts to recall major happenings in his life, and all the women he has loved and left. An autobiographical film of Fellini, about the trials and tribulations of film making. 8 1/2 - Criterion Collection DVD ~ Federico Fellini B00005QAPH One of the greatest films about film ever made, Federico Fellini's 8 1/2 (Otto e Mezzo) turns one man's artistic crisis into a grand epic of the cinema. Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni) is a director whose film-and life-is collapsing around him. An early working title for the film was La Bella Confusione (The Beautiful Confusion), and Fellini's masterpiece is exactly that: a shimmering dream, a circus, and a magic act. The Criterion Collection is proud to present the 1963 Academy Award® winner for Best Foreign-Language Film-one of the most written about, talked about, and imitated movies of all time-in a beautifully restored new digital transfer. Disc two features Fellini's rarely seen first film for television, Fellini: A Director's Notebook (1969). Produced by Peter Goldfarb, this imagined documentary of Fellini is a kaleidoscope of unfinished projects, all of which provide a fascinating and candid window into the director's unique and creative process. SparkNotes: Although 8 1/2 (1963) is director Federico Fellini’s most widely recognized achievement, he was already internationally renowned when he began working on it in late 1960. He had directed La Strada (1954), which won a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar when it was released in the United States three years later, and La Dolce Vita (1960), which had just been released, had won the Palme d’Or (“the Golden Palm,” the award for best film) at the Cannes Film Festival in 1960, and would go on to earn four Oscar nominations. Not surprisingly, as soon as Fellini began jotting his first notes for his “eighth-and-a-half” film (8 1/2 follows six feature-length films and three short films and collaborations), production companies, costume designers, photography directors, and flocks of actresses were hanging around him, eager to stake a claim in the next hit. Cineriz, the production company that had worked with Fellini twice before, expected him to create another cinematic masterpiece. Before Fellini had even outlined the plot of the film, the machinery of its production was already in motion. Fellini was in his early forties, already anxious about typical midlife concerns regarding family, aging, and professional virility, and he felt enormous pressure. This stress was so pervasive that the making of the film became its own principal influence. Fellini had intended the film to describe the crisis of an artist, a journalist, or even a lawyer who is tormented by matrimonial, spiritual, and creative challenges, but he didn’t know how to design the story. La Strada and La Dolce Vita had given Fellini a reputation for ingenuity, and he once again wanted to create something wholly new, as if to prove that he was still in his prime. But as he witnessed the steady physical construction of the film—the sets, the cast, the lighting—he felt increasingly unsure about how he would tell its story. At one point, Fellini decided to quit. When he was in the middle of writing a letter of resignation, however, members of the crew happened to congratulate him on his imminent accomplishment, and the gesture convinced him that he could not abandon the project. Instead, he was inspired by the drama of the moment and decided that the film would be about a director who wants to escape the making of his own movie. Although 81/2 draws on Fellini’s directorial experience, it is also clear that Fellini modeled the personal life of the film’s protagonist, Guido Anselmi, on his own. Guido’s experience in the film is accented with memories of his childhood, and these sequences are consistent with Fellini’s biography. Fellini was born on January 20, 1920, and grew up in Rimini, a city in northern Italy on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. His parents, his father a traveling salesman and his mother a housewife, sent him to parochial school, whose influence appears in two of 8 1/2’s memory sequences. When Fellini was twelve, a circus visited Rimini, and when it left, Fellini went with it. He found work performing as a clown but soon returned to his parents, only to suffer a restless adolescence in the quiet city and leave home again when he was seventeen. This second time, Fellini followed a vaudeville troupe and earned his keep by writing comedy sketches for it. After the troupe performed in Florence, he stayed to write for humor magazines, then went to Milan, where he worked as a cartoonist. The dictator Benito Mussolini had banned American cartoons, so Fellini drew bootleg versions of them. [ Amarcord, AA ] Fellini spent the years of World War II in Rome, where he avoided the military draft and continued to write pieces for humor magazines, as well as for Cico and Pallina, a radio drama. The woman who played Pallina was Giulietta Masina, a fledgling screen actress who would become Fellini’s wife and the star of many of his films, including La Strada and Nights of Cabiria (1956). They married in October 1943 and settled in Rome. Masina continued to look for small movie roles, while Fellini spent his days on the Via Veneto, a luxurious and lively Roman street, peddling caricatures to passersby. Through Vittorio Mussolini, son of the dictator and a close friend of Fellini’s, Fellini met director Roberto Rossellini. Fellini agreed to help Rossellini write his film Open City, which Rossellini completed in 1945... [ sparknotes.com/film/8.5 ] * Filming Inside Guido’s Mind and other pages * Rung, Allison. SparkNote on 8 1/2. 7 Oct. 2005 THEMES script directory: self, family, gender...

The Films of Federico Fellini. Contributors: Peter Bondanella - author. Publisher: Cambridge University Press. 2002. Page Number: 93 --

... "After La dolce vita, however, Fellini turns toward the expression of a personal fantasy world that often, as in the case of 8 1/2, also deals with the representation of cinema itself in a self-reflexive fashion. This turn toward a world more directly taken from his own fantasy owes a great debt to his encounter with Jungian psychoanalysis, which Fellini described as “like the sight of unknown landscapes, like the discovery of a new way of looking at life. ” 1 Fellini had always had a predilection for the irrational, had always experienced a very rich dream life, and under the influence of Jungian psychoanalysis and his encounter with a Roman analyst named Ernest Bernhard, Fellini began to record his numerous dreams, filling large notebooks with colorful sketches made with felt-tip markers that would become a source of inspiration for his art. 2 Fellini preferred Jung to Freud because Jungian psychoanalysis defined the dream not as a symptom of a disease that required a cure but rather as a link to archetypal images shared by all of humanity. For a director whose major goal was to communicate his artistic expression directly to an individual in the audience, no definition of the role of dreams could have greater appeal. The most interesting aspect of Fellini's dream sketches is that they are clearly indebted to the style of early American cartoons, with a touch of De Chirico's metaphysical paintings of deserted Italian squares from the art deco period plus the caricatures of Nino Za that Fellini admired in his youth and imitated as a young man. They not only deal with the obvious subjects one might expect to find in psychoanalysis (sexuality and the role of women in Fellini's fantasy life) but also underline problems of anxiety about artistic creativity."

... "The film Guido seems unable to make is a science-fiction film about the launching of a rocket ship from Earth after a thermonuclear holocaust destroys civilization. A huge rocket launchpad that seems to have no purpose provides a concrete metaphor of Guido's creative impasse. During the many encounters at the spa resort Guido has with his producer, his potential actors, and his production staff, he also finds time for a tryst with his mistress Carla (Sandra Milo), a marital crisis with his estranged wife, Luisa (Anouk Aimée), and a number of embarrassing exchanges with a French intellectual named Daumier (Jean Rougeul), who mercilessly attacks Guido for his artistic confusion, his puerile symbolism, his ideological incoherence, and his lack of any intellectual structure in the film Guido has proposed to make.

In 8 1/2, Fellini makes no pronouncements, presents no theories about art, and avoids the heavy intellectualizing about the nature of the cinema that characterizes so much academic discussion in recent years. As he stated to an interviewer in 1963, 8 1/2 is “extremely simple: it puts forth nothing that needs to be understood or interpreted. ” 7 This would seem to an extraordinarily naïve statement in view of the quantities of pages film historians and critics have devoted to the work, but what Fellini means by his claim is that experiencing 8 1/2 requires no philosophical, aesthetic, or ideological exegesis. Fellini believes receiving the emotional impact of an artist's expression in a work of art is relatively simple. Such communication succeeds when the spectator remains open to new experiences. While feeling an aesthetic experience is relatively simple, given the proper conditions and the disposition of a willing spectator, describing or analyzing such a privileged moment is complex, a rational operation requiring a reliance upon words and concepts that that can never quite measure up to the emotional impact of the work of art itself. For Fellini, the cinema is primarily a visual medium whose emotive power moves through light, not words.

Fellini wants the spectator to assume the point of view of his befuddled film director, Guido Anselmi, and if this identification with a subjective perspective is successful, he is confident that 8 1/2 will provide a most satisfying aesthetic experience. The film's narrative involves the visualization of the process of creativity itself, as we follow Guido's odyssey through his love affair, the crisis of his marriage, and the bewildering complexity of the work on the set of his proposed science-fiction film. Fellini is unconcerned, however, with analyzing the process of creativity; he is interested only in providing images of its process and the powerful emotions of its successful communication to an audience. Thus, he will show the spectator what, in his own experience, it takes to produce a work of art, but he will never provide an ideological explanation or a theoretical justification for this visualization. As he has declared on many occasions, “I don't want to demonstrate anything; I want to show it. ” 8 It is also important to remember that Fellini's visualization of the creative process rests upon comic foundations. The last thing Fellini desired was a pompous discourse on the nature of the aesthetic experience delivered from a pulpit or an academic lectern. During the entire process of filming 8 1/2, Fellini pasted a note to himself on his camera as a pro memoria: “Remember that this is a comic film. ” 9 As a corollary of his emphasis upon visualizing the moment of creativity, Fellini also provides in 8 1/2 a devastating critique of the kind of thinking that goes into film criticism, particularly the kind of ideological criticism so common in France and Italy from the time he began making films up to the moment he began filming 8 1/2.

The process of creativity in 8 1/2 paradoxically involves two different films, in effect. The film that attracts most of our attention is the science-fiction film Guido ultimately never completes. 8 1/2 thus chronicles Guido's inability to create a work of art. However, 8 1/2 also reveals a completed film – Fellini's film about Guido's inability to make his film. In fact, the spectator never sees any of Guido's film. Even the screen tests for the science-fiction picture (shots 600–48) are actually screen tests for Fellini's film about Guido's film. Following Guido throughout most of the narrative does provide the spectator with a thorough grounding in the many problems involved in making a film, including the personal crises and anxieties of the artist involved. Because Fellini believes the unconscious is the ultimate source of artistic creation, particularly experiences from childhood remembered and filtered through the adult sensibility, Guido's childhood experiences are crucial to his adult psyche.

The opening of 8 1/2 underscores the cinematic quality of Fellini's presentation of Guido. The first sequence is a brilliantly re-created nightmare (shots 1–18), in which we see Guido trapped in a car inside a tunnel, initially without any sound, as if in a dream. All around him are strange individuals blocked in a gigantic traffic jam inside the tunnel, some of whom will later be identified as people in his life (Carla, his mistress, for example, who Guido sees being aroused sexually by an older man in a nearby car). Employing his habitual response to anything, Guido attempts to escape by flying up into the sky in a classic flying dream fantasy until he is pulled down to earth by a man who we eventually learn is the press agent for Claudia Cardinale, one of the actresses Guido hopes to put in his film. As Guido suddenly awakens (shots 19–31), he finds himself in his hotel room in a spa where he has gone to take a cure for anxiety, depression, and artistic blockage, and where he is also planning his next film with cast, producer, and production office. We are now supposedly in the “real” world, and it is here that Guido receives a harsh judgment about his proposed film from the French critic Daumier; but the dividing line between fantasy and reality is immediately blurred (shots 32–3) when Guido goes into his bathroom. There, with the glaring lights of a studio arc lamp and the warning buzzer of a sound stage on the sound track, Fellini (Guido's creator) reminds us that Guido's world is actually not real but is part of his (that is, Fellini's) film fantasy. The irrational, the dream state, the magical – as opposed to the rational, “reality, ” and the mundane – constitute the territory staked out by Fellini in his presentation of how Guido attempts to create.

Almost everything about the narrative presenting Guido's work and life emphasizes the role of the irrational in artistic creativity. The costumes of the characters mix styles from different epochs (clothes from the 1930s, the era in which both Fellini's and Guido's childhood take place) and 1962, the present time. This makes it difficult to pin down a time frame. Then the film's editing works against our conventional expectations. There are very few establishing shots upon which we can confidently base our sense of space or place. Constant jumps between the “reality” of Guido's present, his waking visions, his memories of the past, and his fantasies or nightmares do not permit any facile determination of transition from one shot to another. Fellini's extremely mobile camera does not only capture Guido's subjective stream of consciousness, however. When it shifts away from this perspective, it consistently traps Guido within its limiting frame, isolating Guido and underscoring his persistent desire to escape. Meanwhile, other characters seems to move freely in and out of the frame, in contrast to Guido's entrapment. 10 The buzzing sound in the opening bathroom scene that warns us that what we are seeing is a film is repeated throughout the picture: in the hotel lobby (shot 117); in the lobby of the spa (shot 129); when Guido's wife, Luisa, leaves the screen tests (shot 630); and at various times during the showing of the screen tests (shots 603, 643–8). The unfinished sets that are supposed to represent a rocket launchpad, visited by the members of Guido's film (shots 446–73), eventually become in a single brilliant shot (shot 767) a staircase down which all the members of the cast of Guido's film, as well as the production crew of Fellini's film (not Guido's), descend in the concluding sequences of the film. An unusually large number of the film's characters retain the names of the actors who interpret them (Claudia, Agostini, Cesarino, Conocchia, Rossella, Nadine, Mario), an additional element that blurs any clear distinction between fiction and reality. [11 - book's notes]

Everything that is important to learn about Guido is communicated through essentially irrational or magical means, in contrast to the intellectual messages delivered periodically by Daumier, which are thoroughly discredited in the film. An important dream sequence (shots 105–16) places Guido at a cemetery, where his father criticizes him for building a funeral monument that is too small, while his mother kisses him all too passionately and becomes his wife Luisa. Guido suffers not only from guilt but from an Oedipal complex, and his relationship with women is very complex. Later, a performance by a telepath, Maurice (Ian Dallas), correctly reads the phrase Guido has in mind: asa nisi... "

antonioni page

2007 film & movies class

best of fellini :

... Compare Gvido, Kane, Dr. Berg [ how : guide : midterm papers/finals ]

|

8-n-half: 8 1/2 is about Guido Anselmi, an Italian director who has lost all inspiration for his upcoming movie, and it's too late to back out. And aside from the fact that he can't make the film, his mistress, wife, producer, and all the rest of his friends, are pressuring him about one thing or another. So he retreats into his dreams to shelter himself from the pressure, and there, he finds inspiration to make his new film, and face the world.

Marcello Mastroianni .... Guido Anselmi

read 8.5: A Cinematic Odyssey (comments)

... What makes the film interesting is the way in which Fellini ultimately transforms the film as a whole into a commentary on the nature of creativity, art, mid-life crisis, and the battle of the sexes. Throughout the film, the director dreams dreams, has fantasies, and recalls his childhood-and this internal life is presented on the screen with the same sense of reality as reality itself. The staging of the various shots is unique; one is seldom aware that the characters have slipped into a dream, fantasy, or memory until one is well into the scene, and as the film progresses the lines between external life and internal thought become increasingly blurred, with Fellini giving as much (if not more) importance to fantasy as to fact.

The performances and the cinematography are key to the film's success. Even when the film becomes surrealistic, fantastic, the actors perform very realistically and the cinematography presents the scene in keeping with what we understand to be the reality of the characters lives and relationships. At the same time, however, the film has a remarkably poetic quality, a visual fluidity and beauty that transforms even the most ordinary events into something slightly tinged by a dream-like quality. Marcello Mastroianni offers a his greatest performance here, a delicate mixture of desperation and ennui, and he is exceptionally well supported by a cast that includes Claudia Cardinale, Anouk Aimee, and a host of other notables...

Gary F. Taylor "GFT" (Biloxi, MS USA)

Awards: Won 2 Oscars. Another 13 wins & 5 nominations

Nino Rota

Composer (Music Score) + The Godfather Part III

[ pix ]Eight And A Half Comments by Fellini

In the case of 8 1/2, something happened to me which I had feared could happen, but when it did, it was more terrible than I could ever have imagined. I suffered director's block, like writer's block. I had a producer, a contract. I was at Cinecittà, and everybody was ready and waiting for me to make a film. What they didn't know was that the film I was going to make had fled from me. There were sets already up, but I couldn't find my sentimental feeling.

People were asking me about the film. Now, I never answer those questions because I think talking about the film before you do it weakens it, destroys it. The energy goes into the talking. Also, I have to be free to change. Sometimes with the press, as with strangers, I would simply tell them the same lie as to what the film was about-just to stop the questions and to protect my film. Even if I had told them the truth, it would probably have changed so much in the finished film that they would say, "Fellini lied to us." But this was different. This time, I was stammering and saying nonsensical things when Mastroianni asked me about his part. He was so trusting. They all trusted me.

I sat down and started to write a letter to Angelo Rizzoli, admitting the state I was in. I said to him, "Please accept my state of confusion. I can't go on."

Before I could send the letter one of the grips came to fetch me. He said, "You must come to our party." The grips and electricians were having a birthday party for one of them. I wasn't in the mood for anything, but I couldn't say no.

They were serving spumante in paper cups, and I was given one. Then there was a toast, and everyone raised his paper cup. I thought they were going to toast the person having the birthday, but instead they toasted me and my "masterpiece." Of course they had no idea what I was going to do, but they had perfect faith in me. I left to return to my office, stunned.

I was about to cost all of these people their jobs. They called me the Magician. Where was my "magic"? Now what do I do? I asked myself.

But myself didn't answer. I listened to a fountain and the sound of the water, and tried to hear my own inner voice. Then, I heard the small voice of creativity within me. I knew. The story I would tell was of a writer who doesn't know what he wants to write.

I tore up my letter to Rizzoli.

Later, I changed the profession of Guido to that of film director. He became a film director who didn't know what he wanted to direct. It's difficult to portray a writer on the screen, doing what he does in an interesting way. There isn't much action to show in writing. The world of the film director opened up limitless possibilities.

The relationship between Guido and Luisa has to show what once was there between them and what is left over in their relationship. It is still very much a relationship, though it has undergone changes from the days of courtship and the honeymoon. It's difficult to show the bond between a husband and wife who married because of romance and passion, but who have now been married a long time. A friendship largely replaces what was there before, but not totally. It's a friendship for a lifetime, but when feelings of betrayal enter into it . . .

Marcello and Anouk are excellent actors who could pretend. I cannot say, however, that I minded that the two of them found each other so attractive. I think some of that was caught on the screen. Of course, Mastroianni and Anita Ekberg didn't find each other so attractive in real life, and certainly there wasn't anything going on between them, yet La Dolce Vita worked.

I had a different ending in mind for 8 1/2, but I was required to film something for a trailer. For this trailer, I brought back two hundred actors and photographed them as they paraded before seven cameras. When I saw the footage, I was impressed. The rushes were so good, I changed the original ending, which took place in a railroad dining car where Guido and Luisa establish a rapprochement. So, sometimes even a producer's request can have a beneficial effect. I was able to use some of the discarded material in City of Women. The segment in which Snaporaz thinks he sees the women from his dream sitting in his railway compartment was inspired by a segment of Guido thinking he sees all the women from his life sitting in the dining car, which was to have been the end of 8 1/2.

* From I, Fellini (1995) by Charlotte Chandler. Reprinted by permission of the author.

|

| From Fellini |

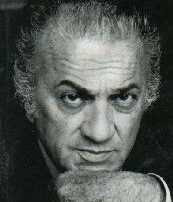

Federico Fellini:

A Bibliography of Materials in the UC Berkeley Library

http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/MRC/fellini.html

|

| From Cinema |

The Fear of Aging:

Guido’s first words in the film are “forty-three,” his age. The placement of this detail so early in the film indicates Guido’s preoccupation with it. A recent onset of health problems (he is ostensibly visiting the spa for a mild liver ailment) causes Guido to worry, like any middle-aged man, that his most productive years are coming to a close. The idea of aging is especially terrifying for a man like Guido, because two of the qualities that he values most—his creative ability and his virility—often rely heavily on youth. Fellini makes some direct references to the physical characteristics of Guido’s aging, as when Guido gazes at his wrinkles in his bathroom mirror, when Mezzabotta comments on his gray hair, and when Claudia teases him that he dresses like an old man. Fellini makes a stronger statement, however, with Guido’s response to the sickly guests at the spa and to his aging companions, Mezzabotta and Conocchia. Mezzabotta’s age is emphasized by his much younger American fiancée Gloria, in whose presence he often comes across as ridiculous or pathetic. When Mezzabotta follows Gloria’s lead on the dance floor and performs some vigorous steps, for example, Fellini frames his sweaty efforts from an unbecoming head-on angle to indicate that Guido thinks Mezzabotta is making a spectacle of himself and aging disgracefully. Guido expresses a similar feeling toward Conocchia, his senior collaborator, who embodies Guido’s fear that getting old will diminish his professional relevance.

[ ... ]

The Tyranny of the Mind:

Fellini’s subjective technique of documenting Guido’s train of thought from reality to daydream and back again, unburdened from traditional perspective shifts and dramatic convention, seems liberating when we view 8 1/2. This placement of daydream and reality side by side comes across as a very convincing depiction of the way in which we actually experience life, reminding us of the mind’s power to transcend everyday reality. But at the same time, the film makes this process, in which observation alternates with imagination, seem somewhat frightening, as it is something over which we have little control. For example, Guido would never choose to have the nightmare of the opening sequence or to imagine his colleagues in the steam baths as hell-bound invalids. His thoughts and daydreams are involuntary. Though this aspect of the mind cannot be consciously controlled, it is interesting to observe the manner in which the subconscious directs it. In the Saraghina sequence, for example, Guido’s subconscious alters the memory to make himself seem more innocent. In Guido’s fantasies about Claudia, excess sound is silenced so that Guido can focus more closely on her. Guido’s dreams seem designed in order to call his attention to his problems. In this way the control of the mind seems constructive, yet the idea of having no free will is frightening.

The Frivolity of Society:

Critics applauded Fellini’s adept and witty social commentary in La Dolce Vita, and the same element exists in 8 1/2 to emphasize the frivolity of bourgeois society. While guests of a ritzy health spa and people in the film industry may seem like easy targets, the elements that Fellini satirizes are relevant to middle- and upper-class society in general. Fellini embeds his satirical references in dialogue that is sometimes off-screen, making it easy to miss. For example, while Guido eyes Carla at the first grand evening at the hotel, we hear the voices of the American reporter and his wife, an American society woman who writes for women’s magazines. The American reporter is speaking to the French actress and her manager in French, expressing the simple opinion that a film should have a hero. His wife interrupts him twice with her nasal cawing, first with “What the hell are you talking about” then with “I don’t understand a damn bit of that French.” After the second interjection, her husband responds in English with “Oh dear, honey, don’t drink any more.” Fellini’s portrayal of the women’s magazine writer—the standard-setter for millions of women—as a crass drunk points to the foolish herd mentality of contemporary culture. The American reporter’s idle chatting with the French actress in her native tongue makes a subtler point: that reporters will do anything to get their story but really have nothing to say. The couple’s American nationality does not indicate Fellini’s antagonism to America but rather the quick spread of American pop culture worship into Europe.

Motifs

Motifs are recurring structures, contrasts, or literary devices that can help to develop and inform the text’s major themes.

Female Sensuality

The most memorable collective body of characters in 8 1/2 is unquestionably its women, who range from a collegiate waif to a movie star to a simple-minded hotel owner. The harem sequence that showcases these women also illustrates the way in which Guido, like many men, is in some way attracted to every woman he’s ever known. Guido feels guilty about having extramarital interest and at certain points expresses the wish not to have such temptation. Fellini articulates Guido’s incredible difficulty suppressing his desire by emphasizing the sensuality of all of the female characters in the film. Carla, Guido’s ever-available, sumptuously beautiful mistress, is the best example, for she personifies sexual temptation itself. Other, more unlikely women also attract Guido, such as the monstrous Saraghina (Guido likes her thick legs and quick hips) and Guido’s homely aunts, with whom he associates being nurtured. In any case, every scene in the film includes women with special features— shapely backs, crowns of blond hair, beautiful voices—that taunt Guido’s intent to behave.

Catholicism

Though the presence of religion pervades 8 1/2, the film offers no clear religious message—a setup well matched to Guido’s ambiguous attitude toward religion. In short, Guido isn’t sure how he feels about faith and the church. He began moving away from the church as an adolescent, when he discovered that the rigors of devout Catholicism would not accommodate his emerging libido. Despite this early separation, the middle-aged Guido has a deep respect for Catholicism and yearns to understand it. In his dream involving his parents, he is wearing a clerical robe, and before his appearance at the fountain he is touched by a solemn moment he witnesses between the cardinal and his attendants in the elevator. Guido makes sure to seek the cardinal’s advice and approval for the script in his film, but during the interview the cardinal seems distant, commenting on a birdcall and asking Guido questions about his family life. The wisdom of the cardinal seems equally inaccessible in Guido’s daydream of their meeting in the steam baths, during which the cardinal recites biblical quotations in Latin and barely acknowledges Guido. Preoccupied with aging, which inevitably leads to death, Guido makes an earnest effort to understand the religion of his upbringing. Nonetheless, the spirit of Catholicism evades him.

Professional Stress

Guido’s life is fraught with professional concerns. The introductory nightmare sequence during which Guido, blissfully escaping into the clouds, is pulled down by men from the film industry, is a clear symptom of his stress. Although Guido’s occupation involves him perhaps a bit more personally than other jobs would—for his artistic production depends on his professional stability—Fellini’s description of the interminable nagging and never-tied loose ends of Guido’s career is nevertheless universally relevant. For example, during Guido’s physical exam, which takes place directly after the nightmare sequence, Fellini depicts the absurdity of society’s acceptance of jobs that invade the personal sphere. Guido sits, leaning forward with his pajama top pulled over his head so that the doctor can listen to his breathing, and allows his collaborator, Daumier, who is wearing a robe, to come in to talk about the script. The level of intimacy with his coworkers that Guido is accustomed to accept seems almost ridiculous. Fellini completes the statement with a flourish at the end of the scene: Guido escapes his doctor and Daumier by slipping into his bathroom, where he expects to find privacy, but is afforded only a moment to himself before a phone—a phone in the bathroom, no less—begins to ring.

Symbols

Symbols are objects, characters, figures, or colors used to represent abstract ideas or concepts.

Guido’s Nose

Toward the beginning of the mind-reading magicians scene, right after Gloria and Mezzabotta dance together, Guido wears a funny-looking false nose, fondling and tapping it. Guido, bored with the entertainment and his company, has apparently shaped the false nose from a dinner roll. More than a mere idle gesture, making the false nose contributes to the film’s extended Pinocchio metaphor. In the well-known story, when the puppet Pinocchio tells a lie, his nose grows. Guido, thinking of himself as Pinocchio, relates his dishonesty to his nose and taps it with his finger at significant moments. Right before Guido’s first daydream of Claudia serving him spring water, for example, Guido taps his nose. He repeats the gesture at the café right before the harem fantasy. In both instances, Guido is uncomfortable before he plunges into his fantasy, and the fabrication seems to be a sort of defense mechanism for him. Guido’s glasses, which he touches or pulls away from his eyes before moments of fantasy or dishonesty, have a similar symbolic significance.

The Rocket Launch Pad

Since the producers are eager to start shooting Guido’s film, they begin construction of a rocket launch pad that Guido designed even before he had completed a screenplay to accommodate it. As it turns out, Guido realizes that science fiction is the wrong artistic direction for him and gives the orders to tear it down before construction is even complete. The launch pad, which consumed two hundred tons of concrete alone, is a prodigious mistake with important symbolic significance. Like the fabled Tower of Babel, the shuttle is a symbol of arrogance, but rather than signifying Guido’s attempt to be closer to the gods, the shuttle alludes to his creative pretension. Guido spends much of his professional life among doting admirers, and without proper criticism to temper their praise, he feels an excess of artistic license that allows him to “lie,” as he puts it, or to be artistically insincere. The potentially phallic nature of the launch pad apparatus also suggests a reminder of Guido’s sexual arrogance and infidelity.

The Rope

The traffic jam of the opening sequence represents the suffocating presence of the film industry in Guido’s life, which he escapes miraculously by floating into the sky. He is free for only a few moments before two businessmen, the manager and the publicist for actress Claudia Cardinale, yank him back down to Earth with a rope. Guido struggles briefly with the rope before he descends. The rope serves as a symbol of the film industry’s control and near ownership of Guido’s life. The producers who fund Guido’s creative projects nag him, the press never leaves him alone, and Guido himself is tied to his movies by his own concerns about artistic integrity. Toward the end of the film, during the screen tests, Guido takes advantage of a delicious opportunity to reverse the rope’s symbolic function when he imagines his producers using it to hang the irritating Daumier.

The Spring

Fellini was interested in the work of Carl Jung, the psychologist who wrote that the anima (the repressed feminine component of the male unconscious mind) is responsible for the connection to the spring, or source of life, in the unconscious mind. Likewise, the supposedly curative spring in 8 1/2 has symbolic meaning that is at once related to female psychology and youth. The spring, then, is a perfectly appropriate “cure” for Guido’s major challenges, which include confusion with women and fear of aging. Claudia Cardinale, whom Guido plans to cast as his lead actress, is a personification of these qualities of the spring. This link between Claudia and the spring is especially clear in Guido’s fantasy of her in his bedroom, during which she repeats, “I want to create order, I want to cleanse.” The moment when Guido decides not to include Claudia in his film is thus doubly meaningful because while it marks his creative revelation, it also signifies his realization that there is no simple “cure” to his challenges.

The Films of Federico Fellini

Book by Peter Bondanella; Cambridge University Press, 2002 :

... "Yet another journey into Guido's subconscious reveals even more interesting information about his views on sexuality and women. After daydreaming about a meeting of his wife and mistress, in which both are supremely friendly and happy (shots 504–8), a scene that is enacted before Guido at a café, we shift abruptly to the justly famous harem sequence (shots 509–74), the ultimate fantasy for an Italian male like Guido. The setting is the same farmhouse we have seen earlier, when the young Guido was bathed in a wine vat and lovingly put to bed. Now all the women in his life – his mistress, his wife, the actresses in his films, chance acquaintances he has met (including a Danish airline stewardess) – all gather together to serve his needs, pander to his every wish, and do whatever he likes to give him a sense of superiority and well-being. They even pretend to rebel so that he can dominate them with a bullwhip in a performance that is reenacted each evening. "

..."Visualizing Guido's fantasies serves Fellini as a visualization of the sources of all artistic creativity. These sources are primarily from childhood, an unsurprising statement for a creative artist. They are primarily visual images, not ideas, and they may be triggered by any free association in the present – a tune, a picture, a word, anything that reminds the artist of something buried deeply in his or her psyche. Such images are essentially undisciplined and confusing, since they enter the artist's stream of consciousness without any particular order or timing. The entire narrative of 8 1/2 may be said to illustrate how such images filter into our lives without warning and without any predictable relationship to one another. Critical thought is required to order and to discipline such raw material, but it is critical thought of a particularly nonacademic kind. This necessary kind of discipline will only be visualized but not defined by Fellini at the conclusion of 8 1/2. "

... "The conclusion of 8 1/2 is indeed a magical moment, introduced by a telepath, energized by Nino Rota's unforgettable circus music, and carried off by a director who must be considered both part magician and part con man. Paradoxically, everything Daumier has said about Guido's film (and Fellini's film, since Guido is an alter ego for Fellini throughout the work) is basically true. The entire film is filled with pointed attacks upon the kind of thinking inherent in Fellini's artistic creations, including all his intellectual deficiencies, his mental tics, and his visual obsessions. However, when the spectator concentrates upon what Fellini makes his audience see in 8 1/2, especially this magical visualization of the moment of artistic creation – an essentially irrational, illogical, and ultimately inexplicable epiphany – Daumier's objections dissolve as if by magic. As the great showman he is, Fellini realizes that he can sweep away our intellectual uncertainties with a moving visual image, and this is exactly what he accomplishes throughout the many encounters with Daumier, culminating with the grand finale of 8 1/2. "

Amarcord

Nostalgia and Politics

Fellini: “Especially as regards passion for politics, I am more Eskimo than Roman…. I am not a political person, have never been one. Politics and sports leave me completely cold, indifferent.”

... “I believe a person with an artistic bent is naturally conservative and needs order around him…. I need order because I am a transgressor … to carry out my transgressions I need very strict order, with many taboos, obstacles at every step, moralizing, processions, alpine choruses filing along.”

... Because Fellini is primarily an artist and not an ideologue, it is not surprising that the few basic beliefs he holds in this regard are rooted ultimately in his aesthetics. As we have seen from our discussion of 8 1/2, Fellini locates the focal point of creativity in the individual and his fantasy life. Consequently, anything that deforms, obstructs, represses, or distorts this creativity or the growth of a free consciousness within the individuals making up society is to be opposed:

I believe – please note, I am only supposing – that what I care about most is the freedom of man, the liberation of the individual man from the network of moral and social convention in which he believes, or rather in which he thinks he believes, and which encloses him and limits him and makes him seem narrower, smaller, sometimes even worse than he really is. If you really want me to turn teacher, then condense it with these words: be what you are, that is, discover yourself, in order to love life.[ video clip from youtube.com -- Fellini ]

[ hard drive ]

... All of Fellini's films, as the director noted in a letter about Amarcord to the Italian critic Gian Luigi Rondi, “have the tendency to demolish preconceived ideas, rhetoric, diagrams, taboos, the abhorrent forms of a certain type of upbringing...

6. "Intervista"

A Summation of a Cinematic Career

...